In Conversation with Paul Pearson

The Occult Library recently sat down for a conversation with Paul Pearson.

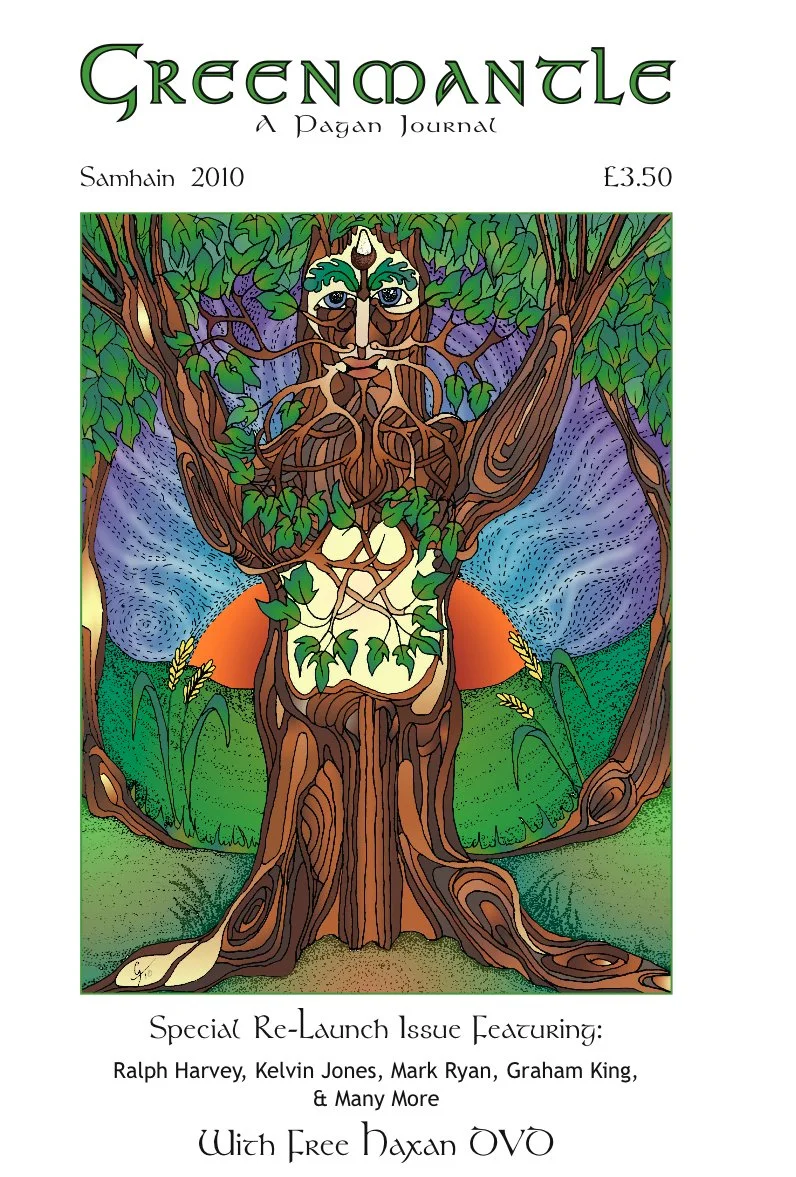

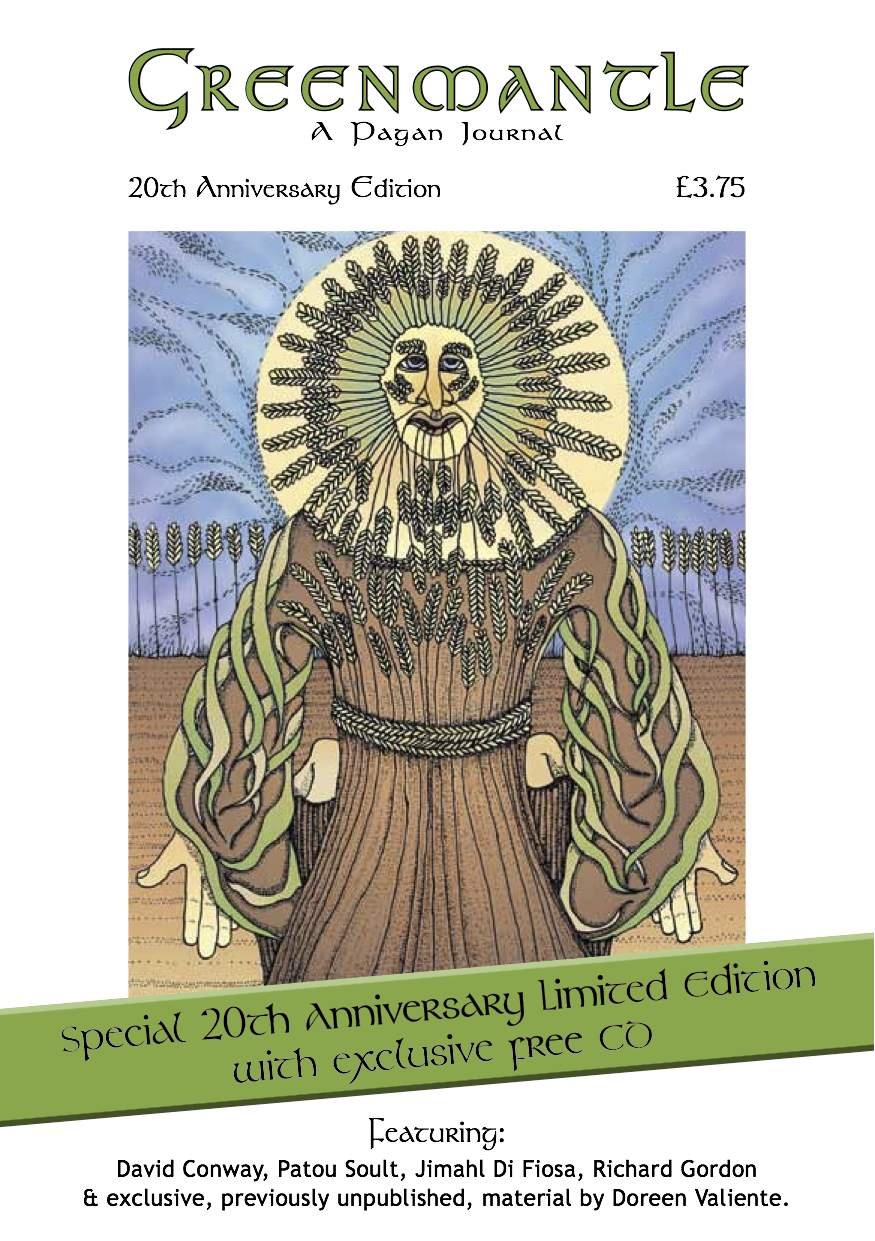

Paul is a writer, and serves as the editor of the U.K.-based pagan publication Greenmantle: A Pagan Journal. The publication is “…a magazine for Pagans and occultists of all beliefs, paths and denominations. Founded in 1993, it has a unique voice combining thought-provoking and intelligent articles with news, humour, and a light-hearted personal touch.”

Paul has also served as a trustee and collaborator with numerous pagan organizations, meetings, and moots such as PaganAid, The Pagan Federation, the Pagan and Heathen Symposium, and The Doreen Valiente Foundation.

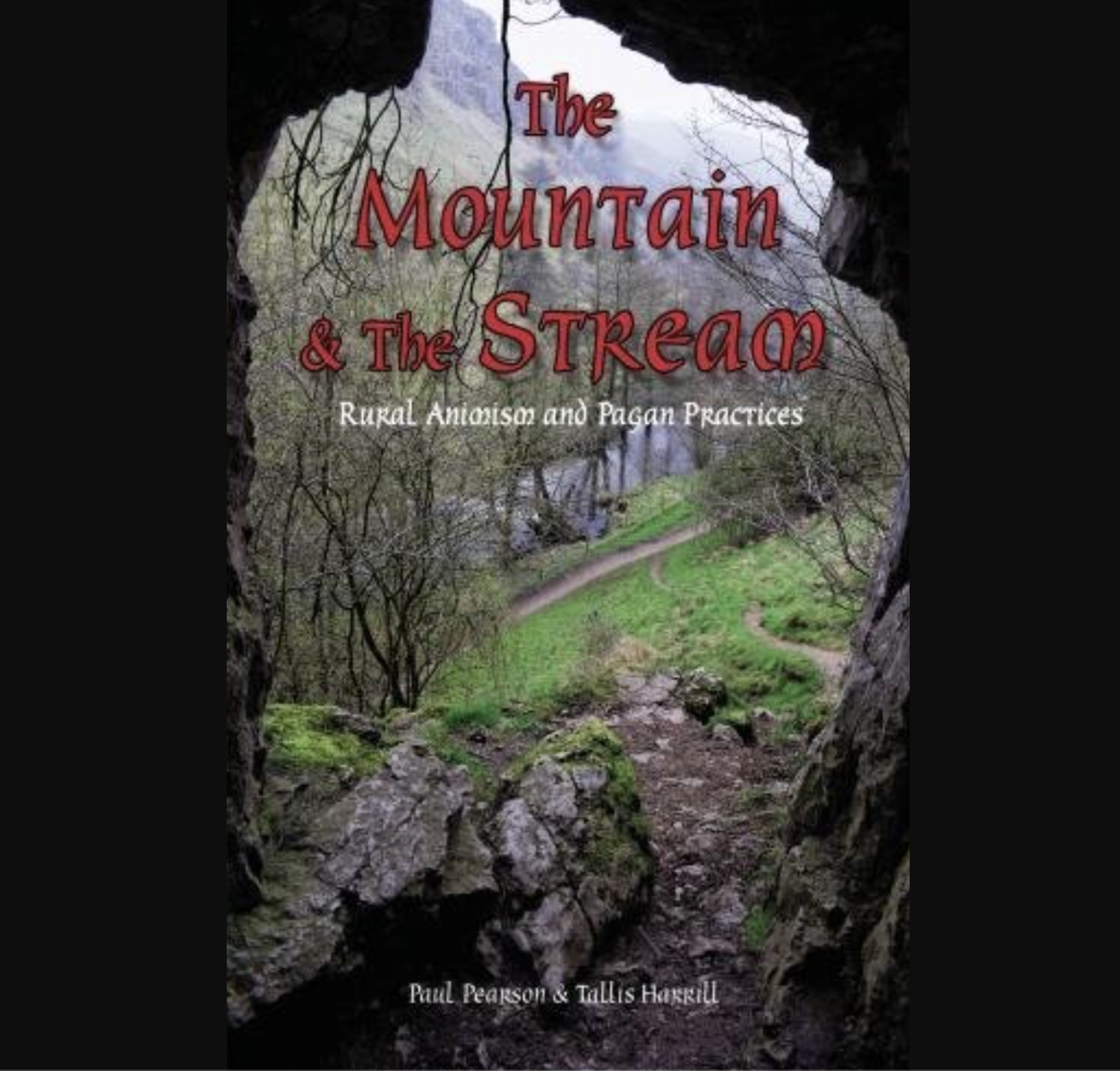

In the guise of long-form publishing, Paul and his co-author and friend Tallis Harril notably published The Mountain and The Stream: Rural Animisan and Pagan Practises in 2017.

Paul’s experiences in this area grew out of a lifelong connection with the land, music, and the vivacity of the pagan community — notably the pagan festival scene in the U.K. over a number of decades. In our conversation, we discuss these topics and more. We hope you will enjoy the discussion.

OL: Hello there Paul. Thank you for taking the time to discuss your work with us today. Your own work centers on rural animism and paganism. Can you recall how your own sense of rurality developed at a young age? Had there, early on, been a sense of ‘aliveness’ in the land you resided and explored?

PP: A pleasure. As a child I was a lover of myths and legends which engendered an interest in ancient sites and the landscape. Being brought up on the Stretford, a town on the edge of the industrial area of Trafford Park, the closest countryside was in the local meadows close to the River Mersey, which was a childhood haunt in the summer holidays. Annual family holidays were usually in Devon and Cornwall and the countryside and rural community were very special to me.

However, it was the reading of the early books of novelist Alan Garner, particularly The Weirdstone of Brisingamen (Collins 1960), a fantasy set in and around Alderley Edge in Cheshire, not too far from where I was living, that introduced me to the physical landscape of the area and the legends therein. I became almost obsessed with the place and its air of magic. It was there I really began to connect with the landscape.

OL: You have previously mentioned your experiences moving to Brighton, becoming embedded with artistic and bohemian circles, and immersing yourself into the pagan festival scene. For those of us among us who could not experience those places and times, what was the atmosphere and camaraderie like at these festival events?

PP: Brighton was a real eye-opener for me. It was vibrant and wonderful at the time. Most people I met and knew were artists, or involved with music and alternative practices. For a city-bred person it was a very liberating experience. Brighton was like an art gallery with a cool hippy-like vibe. It was exciting and inhabited by some amazing people, many who became friends.

Music was a major feature of the town with various small festivals happening in and around the town (now a city) and I was drawn to it — prior to moving to Brighton I was a lover of Pagan-based music. Via the local music scene I was introduced to bands such as Kangaroo Moon, Mandragora, Wildflower and The Levellers and many more. My local venue, The Prince Albert, had a variety of musicians and bands playing at the venue as well as being the meeting place for the local Pagan Fed moots.

Through my new friends I was asked to help with the setup of the site for the Earth Spirit festival in Sussex. The original motivation was to secure a stall for the art group Altar Image, a cooperative group of a handful of artist friends — and of course free entry! After a week or two living in a tent and working hard digging latrines and erecting benders and marquees for the festival, we erected our bender and looked forward to an enjoyable and profitable festival.

The event was a washout — the weather was devastating, and many sought shelter rather than looking at the stalls. But, although all the exhibitors and dealers were losing money and exposure, there was a wonderful camaraderie and friendliness between us and we bartered our wares with each other, rather enjoying the misfortune rather than bemoaning it. There were also events held in the centre of Brighton such as the Occulture festivals, which focused on magical and Pagan studies, which showcased such luminaries such as Ramsey Dukes, Colin Wilson, Ralph Harvey and Amado Crowley, some of who became contributors to Greenmantle.

Greenmantle banner

OL: Can you describe the surge in interest and readership that you experienced shortly after beginning the Greenmantle? What were some of the challenges and rewards of this process?

PP: Greenmantle happened quite by accident by accident. The late Tam Campbell asked to leave his Pagan Federation/Pagan Link literature on our stall (one of the very few that survived the weather) and many people asked us about the Pagan scene in Brighton and its environs. We didn't know of any purely Pagan events or groups at the time, so we took name and details to pass on to Tam on his return. However we didn't see him again, and decided to try and get any details we could find out to those people who had asked. It was when we contacted the local Pagan Federation representatives that things really started moving.

We learned of moots and gatherings such as the annual Broomstick Rally in Plumpton Green (which sadly only lasted a couple of years) and occasional open rituals and we, Patricia Gill (also known as Rowan Wulfe) and myself, decided to create a one-off magazine for the locals who had asked for information, and we passed this info to the local pagan reps. I had done some work on a Pagan contact magazine in Essex (Gates of Annwn) so I had a little experience with magazine production which I put to use on Greenmantle (the title inspired by a Charles de Lint book of the same name), working on an old Amstrad word processor and incorporating the art of Rowan Wulfe.

Printouts and art were laid out by hand - these were the days before the onset of home computing proper, where cut and paste was literally scissors and glue - and the results would be photocopied and sent out. It was a fun project. However, word had already reached the Pagan community and we received a great many enquiries and, before we knew it, this one-off idea had inadvertently spawned an on-going project. It was a challenge, as we hadn't been prepared for anything beyond a single issue, so it became onerous. Doing all the writing myself was not really desirable due to the time and effort involved, so I reached out to my new Pagan friends and managed to get some contributions, though not as many as I would have liked.

Also, an expanding readership led to rising costs, yet I was loathe to make the Pagan community foot the bill and kept prices down to cover most of the costs. In fact, for quite a while the magazine didn't cover the costs of production and I was partly funding it out of my own pocket. I didn't mind this, as I saw it as a service I was doing for the community. However, it was something I was proud of and it opened many doors in the Pagan community, including a great friendship with John Belham Payne, who later went on to create The Centre for Pagan Studies and The Doreen Valiente Foundation, with whom we later collaborated on some projects (including the Doreen Valiente Blue Plaque event in 2013). We were also awarded The Golden Broomstick Award for best Pagan magazine at the Broomstick Rally, where I was also introduced to the music of Seventh Wave.

A typical Greenmantle booth containg various issues of the publication

OL: Speaking of, one incredible facet of your work is the collaborations you have carried out between Greenmantle and musicians in the pagan community. Groups like Legend, Seventh Wave, and Inkubus Sukubus were incorporated into your festivities, and you even offered vinyl records. Did you see this collaboration between artists and musicians as essential to the aims of both the community and the publication?

PP: My collaboration with the music scene actually started when I worked on Gates of Annwn in Essex. I was introduced to the music of Children of the Moon (later to become Inkubus Sukkubus). Some years previously I wrote a musical based on Alan Garner's Weirdstone of Brisingamen, called Firefrost, and I wanted to rearrange the music for a potential new production and quite liked the idea of doing it with Children of the Moon. I phoned Tony McCormack who was interested in the idea and sent the score to him. He produced a few, newly arranged songs. (As a footnote, one of the original musical arrangers of the original Manchester production, Azhar el Saffar, was in attendance at the Earth Spirit Festival — I hadn't seen her since the production — and she was involved in a Pagan band, Wildflower, and we rekindled our friendship).

The project failed to happen due to rights issues with Alan Garner's agent. However, I still had hopes to release the music on cassette, but Incubus Succubus (as they were before changing the spelling of the group's name) were too busy on their new album but put me in touch with Steve Paine who was producing the new album. Steve ran a recording company and record label Pagan Media, and headed the Pagan prog band Legend. Although the idea of releasing the Firefrost music fell by the wayside we enjoyed (and still do) a great friendship and which arose from our collaborations. I introduced Steve to the music of Talis Kimberley, whose music we reviewed and who had performed for us, and they too collaborated on projects, including a couple of CDs which we gave away free with the magazine. Shortly after, I was introduced to Seventh Wave at a Broomstick Rally who, for reasons beyond my comprehension, asked me to be their manager. This led to the group often playing alongside Legend and Incubus Succubus.

Music, I think, has become an integral part of the Pagan community, and it is rare to find a Pagan event, nowadays, without music. For the magazine it was certainly a boon and by sharing it, via free flexi-discs and CDs with the magazine, it helped both the musicians with exposure, and brought fans of their music to the magazine. The exposure to the music and musicians, I think, is another avenue helping the positive view of Paganism to the general community. Some music fans, especially in the Goth and Folk circles often find their way into the Pagan scene and its spirituality through discovering the music. Even some mainstream artists have incorporated Paganism and Pagan symbolism into their work, so I think the community benefits from this positive representation. The rise in Pagan-themed music indicates the demand for it, with groups such as Faun, and Within Temptation, Haxan, Chantras and several other groups — with genres such as rock, folk and even jazz — on the rise.

The Samhain 2010 issue of Greenmantle

OL: Looking back on the 30-odd years since that 1993 Earth Spirit Festival, what surprises you the most about the longevity of Greenmantle? Perhaps it speaks to the unceasing role of the printed and written word within pagan communities?

PP: I think Greenmantle's longevity is partly due to its sincerity, partly its aversion to covering topics that have been overused in Pagan magazines (such as "how to read runes/tarot" etc), steering clear of poetry and fiction (with the excption of two poems from Doreen Valiente), and its friendliness. We have a deep respect for our readers and consider them friends — we don't treat them as just customers and quite often meet, chat, socialize and even invite them to visit. Another key element for our continuing longevity is, I believe, because we are still a physical magazine. We have seen so many publications fold or transfer to just digital issues. One negative side for us — with many physical magazines we shared a reciprocal exchange feature, wherein each publisher would share copies of their publication for a mention in each other's magazine, thus getting the titles to a wider audience. Like me, readers like to have something physical. Curiously, The Mountain and the Stream has not sold a single Kindle copy, and the number of reprints certainly indicate most people are happier with the physical medium.

The 20th anniversary issue of Greenmantle

OL: Paul, in 2020 you published the aforementioned book with Tallis Harrill, The Mountain and the Stream: Rural Animism and Pagan Practices. How did your work with Greenmantle inform a larger, full-length text? Was the editing and writing process aided by many years of practice and refinement?

The Mountain and the Stream: Rural Animism and Pagan Practices

PP: The Mountain and the Stream originally had very little to do with Greenmantle. In fact, in the period when it was first conceived in Tuscany, I was considering shelving the magazine. I have always written for magazines, small publications and for the stage, so the composition was relatively easy, but the creation was a longer process. Originally it played with theories and ideas that were ultimately discarded. It really took shape when we moved to the Peak District and the roots if my earlier magical life gave resonance to the themes explored.

When first conceived, the book was dealing with the rural Tuscan system and comparing it to the standard ideas and practices of Wicca. Once back in the Peak District we realized that the core should really compare the Tuscan and the rural Cheshire traditions of my past and fusing it with Animism. Once the main core was in place, and Tallis contributed her sections, it finally became a whole. The editing was done by Tallis — I do have a habit of going off on tangents when writing, but Tallis was able to hold me in check!

OL: One aim of your book involves the linkage of modern pagan practices with the animist traditions of old. To perhaps link this discussion back to those pagan festivals of the 1990’s, how do you feel that pagan communities and practices at the turn of this century have best carried out this task?

PP: In my early magical years, witchcraft and other Pagan traditions often stated that their religions were nature religions, yet ironically, the natural world seemed to take a back seat in many magical practices. Wiccans would echo the 'nature religion' soundbite, yet many actually concentrated on specific deities and practices which took place in front rooms, using tools and rituals which seemed more appropriate to classical or ceremonial traditions: relying on psychodrama, concentrating on precision in rituals, tools, and robes. All of these have their place in magical work. Yet, aside from the occasional foray into the countryside, there was little actual connection to the landscape within the framework of the actual work.

Nowadays, Animism is thankfully bringing the nature back into nature religions, with more and more people experiencing a connection with the land and its latent energies. Even Christians who have read our book understand the relationship with the land without straying from their Christian roots. From an ecological point of view this is good news, as there is a greater respect for the landscape and the environmental impact of modern society

OL: Finally, Paul, you have initiatory roots in these traditions of Tuscany. As a British pagan, how do you find a linkage between these two realms or landscape and practice? Do you feel that the animist lifeway holds a vital current which links landscapes in this way?

PP: Yes indeed — the rise in the interest in animism brings a convergence of the Pagan spirituality resounding with the land, creating a liminal bridge spanning ancient energies with a modern accent. The similarities shared with the British and Tuscan, are very similar in the core of their spiritual paths. The landscape may differ but the central concepts remain the same — that being the finding of the spiritual in the landscape and reacting with it.

OL: Paul, we are deeply grateful for the chance to speak today. Thank you for sharing your insights, and best of luck with your future endeavors.

PP: Thank you — My pleasure.

Paul Pearson’s work with Greenmantle, including current and previous issues, adjacent publications, subscription information, and events can be found via greenmantle.org.uk.

The Occult Library is grateful to Paul’s generous time, and we look forward to speaking in the future.